Introduction

Why do you need an imaging test for thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) to assess soft tissues and rule out differential diagnoses like spinal cord issues? Curious about how this diagnostic tool can provide crucial insights into your health? Imaging tests play a vital role in identifying TOS, guiding treatment decisions, and ensuring accurate diagnosis of soft tissues for doctors and differential diagnoses.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

When patients leave Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis after Dr. Robert Thompson, a vascular surgeon, has removed their first rib as part of thoracic outlet decompression surgery, they are given the 4-centimeter piece of bone to take home as a memento, along with detailed instructions on how to care for it. First, soak it in ammonia to remove any residual blood and oil from the bone. Then, use peroxide to whiten it. Finally, apply a coat of Mop & Glo to prevent any oils or dirt from staining the bone. Yes, Mop & Glo — the stuff used to shine up kitchen floors.

Focus on the First Rib

This is a relatively straightforward article published on the official Major League Baseball website. The author focuses on the first rib fragment that was removed by Dr. Robert Thompson and provided to pitcher Matt Harvey following his surgery. Quotes from Harvey, along with background information from Dr. Thompson, are used to introduce the reader to the basics of TOS and TOS surgery.

I found some of the background information interesting. Obviously, this material has been simplified for the lay-people who are expected to read the article.

Delays in the Diagnosis of TOS

Thoracic outlet syndrome has been quite overlooked, especially in the professional athlete, because something always hurts,” said Thompson. “A person with thoracic outlet syndrome might have pain in the shoulder, and might have an MRI that shows mild to moderate changes — and might even have shoulder surgery for something else, like a rotator cuff or a labrum. Only when that doesn’t correct the problem do they look for TOS.”

I agree with Dr. Thompson that many TOS patients do not get a timely diagnosis. Many doctors look first for diagnoses with which they are familiar. There is limited awareness of thoracic outlet syndrome in many medical communities. As a result, doctors may perform many diagnostic tests, or even surgery, before they even consider the diagnosis of TOS. And this delay doesn’t just occur in professional athletes. There are likely a large number of people with TOS who struggle for some time before they receive the correct diagnosis.

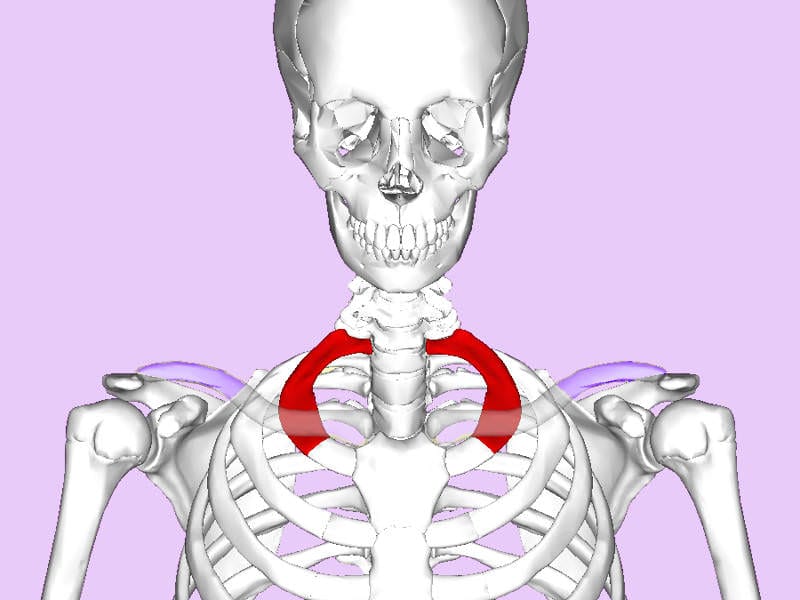

Can we find anomalies and see the space in the thoracic outlet?

Those who develop TOS often have a congenital variation in their anatomy that predisposes them to the condition; in other words, there is just less space in the thoracic outlet to begin with. TOS can also be the result of either a repetitive strain or acute injury that results in scarring, tightness and spasm of the scalene muscles, which attach to the first rib. When the scalene muscles are tight, they pull the first rib closer to the collar bone, causing less space in the thoracic outlet and more compression of the structures within.

There is no ‘gold standard’ for the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. Clinical tests such as Adson’s test are known to have low accuracy. No lab test or electrophysiologic test has proven accuracy. This article references a publication by Thompson, et al that states, “…the diagnosis is based largely on the exclusion of other conditions and a recognition of stereotypical clinical patterns.” Well, that is no gold standard, either.

It should be obvious that I am an advocate of modern diagnostic imaging in patients with TOS. However, there remains a lot of resistance to such imaging, despite the lack of a gold standard. As an example, in 2016, the Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome: Executive summary stated the following regarding diagnostic imaging of patients with neurogenic TOS:

“A chest radiograph or cervical spine series should be performed in all patients and the presence or absence of a cervical rib or elongated C7 transverse process reported”

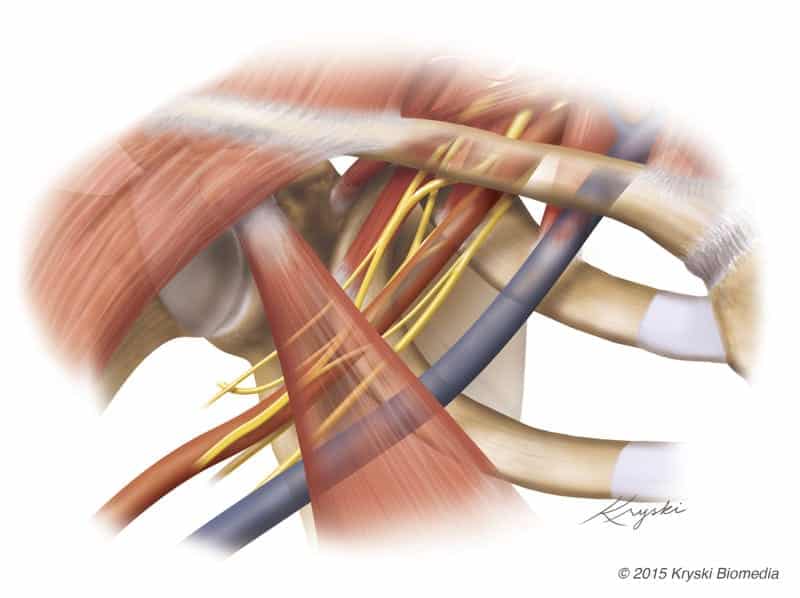

Researchers first demonstrated congenital soft tissue variations in the thoracic outlet more than a century ago. TOS authorities widely accept the fact that such variations may cause compression or tension on the brachial plexus, resulting in neurogenic TOS. This mechanism of nerve entrapment is well-known in other areas of the body.

Can you see any congenital soft tissue variations in this radiograph? I can’t.

Cervical ribs and elongated C7 transverse processes are relatively common in humans. About o.5 to 1% of people have them, and most of these people do not have TOS. Looked at another way, most TOS patients do not have these bony variations. The presence of a cervical rib does not rule in or rule out TOS.

Radiographs were first performed in 1895. They show bones with good detail. They cannot demonstrate congenital soft tissue variations or compression of the brachial plexus.

Today, we use MRI for almost all diagnostic imaging involving soft tissue structures. MRI is widely used for assessing knee ligaments, the rotator cuff of the shoulder, or elbow ligament damage in baseball pitchers. MRI has been proven accurate in assessing the soft tissues of the thoracic outlet.

Scalene muscles may become ‘tight,’ but the stated effect of pulling “the first rib closer to the collar bone.” is purely conjecture. The anterior scalene muscle originates on the cervical spine and inserts on the first rib. While the cervical spine is flexible, the first rib is rather tightly bound to the entire rib cage. Should the anterior scalene muscle contract, it is far more likely that the neck would flex forward than the entire rib cage would elevate. Additionally, the position of the clavicle is independent of the anterior scalene muscle. To the best of my knowledge, there is no published evidence of the first rib being elevated by a ‘tight’ anterior scalene muscle. Nonetheless, radiographs cannot show the space between the first rib and clavicle. MRI has been proven to show this space, as well as the brachial plexus that passes through this space.

Pitcher effectiveness following TOS surgery

The only study of thoracic outlet syndrome in MLB pitchers was done by Thompson with help from the statisticians at PITCHf/x, and it was published in February. All 13 MLB pitchers known to have had the surgery at the time were included in the study. Of them, 10 returned to play in the Majors after the procedure. There were no significant differences pre- and post-op for 15 traditional pitching metrics — including ERA, WHIP, BB/9 and strikeout-to-walk ratio.

We will discuss this article in a later, more detailed post. For now, we could discuss a few things about this article.

First, the sample size is necessarily small. There simply aren’t that many major-league pitchers walking around.

Second, of the thirteen pitchers who underwent surgery, 3 never returned to pitch. Statistical analysis was performed without the three dropouts.

Third, no data was included on the length of symptoms related to TOS, or when the diagnosis was first made. As noted by Dr. Thompson earlier in this article, diagnosis of TOS often takes some time. Therefore, the time periods used for statistical comparison in this study are arbitrary, not necessarily related to the presence of TOS.

Finally, considering the last point, we cannot know if we are comparing post-operative statistics to statistics during a HEALTHY pre-operative period. In other words, what were the pitcher’s statistics when he was healthy, before he developed TOS? Without knowing how long TOS has been present, we cannot know if the pre-operative stats were a mix of ‘healthy’ and ‘TOS’ stats.

Summary and key points

The article was published on the Major League Baseball website. I feel there’s a certain bias towards simplifying and normalizing TOS surgery. Although the writer tried to humanize the procedure and its outcome, we should remember that first rib resection is a significant procedure.

Some of the underlying background material is not accurate or scientifically proven. Surgery for neurogenic TOS remains one of the few major procedures that is undertaken without modern diagnostic imaging. There is no logical support for this approach, in my opinion.

Outcomes from surgery in these elite athletes remain unclear. Even the authors of the article referenced here caution against taking too much from their data.

Given the prominence of sports in our modern-day culture, I hope that every article about TOS raises awareness among lay-people and professional. We certainly have room to grow.